“All filmmaking is based on a lie,” says Israeli Professor Nitzan Ben-Shaul. “In the narrative structure of a movie, it appears that there is only one possible ending – that the way it’s presented is the way it has to be. But in life there are always options.”

To demonstrate his argument, Ben-Shaul of the Film and Television Department at Tel Aviv University has created the world’s first, fully interactive feature film where the viewer gets to decide at various points, in real time, how the action will progress. “It’s nothing short of revolutionary,” he says. “It has the possibility of turning every one of us into potential film directors.”

Ben-Shaul is not a technologist – he teaches classes in cinema studies at Tel Aviv University and has written several books including Mythical Expressions of Siege in Israeli Films and Hyper-Narrative Interactive Cinema: Problems and Solution. So to create his interactive movie, he partnered with Guy Avneyon who built a sophisticated patent-pending movie editor and standalone player.

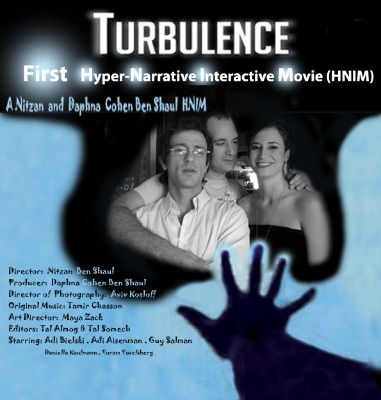

The technology is still under construction, as is the company. Turbulence (also the name of Ben-Shaul’s interactive film) is just now being incorporated and seeking angel investment. For Ben-Shaul, that’s less important. His focus is the process of thinking through the making of an interactive movie.

Ben-Shaul points to the Gwyneth Paltrow hit Sliding Doors which presented two alternative paths that intersected, diverged and eventually arrived at a single conclusion.

Turbulence the film is similar, except that the viewer controls the points of departure. The 83-minute suspense/thriller is about three friends who meet by chance in New York 20 years after they participated in a demonstration in Israel and were arrested. At the time, the police pitted the three against each other, which led to accusations of betrayal. There is also a love story that is rekindled.

The interaction takes the form of “hot spots” that glow when the viewer can make a choice. At one point, for example, one of the Israelis has written a message to his lover on his cell phone. The viewer can click “Send” or “Cancel”. If the viewer hesitates too long, the action continues according to a pre-determined narrative path.

Unlike previous interactive attempts, the transitions in Turbulence are seamless, which means there is no point where the movie stops and a flashing button appears with big icons to click. Once a choice is made, the film immediately cuts to a new scene. “That’s the language of movies,” Ben-Shaul explains. “There could be 4,000 cuts in a film, but if you cut on motion, people don’t see the transition, they just see the flow.”

While viewers make choices throughout the viewing experience, the film regularly returns to the main narrative. This means the writers don’t have to create 10 entirely different scripts (although in Turbulence there are several alternate endings).

Ben-Shaul is adamant that interactivity is not a gimmick – like the first attempts at 3D in the 1950s and 1960s. But he warns that interactive films must be carefully planned to avoid the errors of more primitive experiments in the past.

These mistakes include what he refers to as the ‘computerization trap’. “Computers can generate endless possibilities, but that doesn’t help the viewer in terms of drama. It interests computers, but not humans!” he says. Good interactive drama, he adds, is actually about “option restriction”.

Interactive movie producers should also not try to emulate the gaming world, he cautions. “It’s not about scoring and puzzle-solving,” Ben-Shaul says. “It’s about creating real, life-like situations.”

Turbulence can currently be viewed on either a Mac or PC. But Ben-Shaul is most excited about the red-hot Apple iPad. With its touch screen and media consumption emphasis, “it’s the perfect device. The iPad is a main target,” Ben-Shaul says.

The technological secret behind the film comprises an editor that will be familiar to anyone who’s ever created a movie, with a timeline, audio control, and multiple tracks. There are various additions such as a library of clips and hot spots that can be easily inserted.

The aim is to sell a standalone version as well as plug-ins for professional editing systems such as Final Cut Pro, Adobe Premiere and Avid. Ben-Shaul and his team are also developing a scriptwriting tool that will ease the creation of a hyper-narrative.

Both grassroots and professional filmmakers should be empowered. “We’re not aiming toward automatic storytelling,” he says. “That’s like robots today, which are so far off from what humans can do.”

Turbulence isn’t the only software company making interactive movies. Israeli alternative rock sensation Yoni Bloch owns a company called Interlude, which is moving in the same direction. Earlier this year, Interlude produced a music video by pop singer Andy Grammar that includes seamless interactivity. YouTube also has its own very simple interactive functionality.

Ben-Shaul acknowledges the competition but says his system is further along, not to mention patented. Turbulence also gives viewers the ability to actually move an object on screen (for example, to slide a letter out of a drawer) rather than just click or touch a point on the screen.

The idea for Turbulence was hatched in response to one of Ben-Shaul’s courses about the “siege mentality in Israeli cinema.” The professor explains: “Israeli movies are very close-minded. It comes from the society and the political situation; from war and ethnic tensions. Interactivity and giving people options is the opposite.”

Interactive movies are primarily intended for an audience of one. But Ben-Shaul says it’s possible for an entire audience to get in on the fun. Turbulence was premiered at the Berkeley Film Festival this year where it won the prize for “best experimental feature.”

In a demonstration of the interactivity at the showing, Ben-Shaul’s wife (who also works at the company) canvassed the audience at each decision point. Ben-Shaul then clicked the viewer’s choice from his computer backstage.

In the future, Ben-Shaul would like to build a system where everyone in the audience has a controller, allowing the movie to move in the direction dictated by a majority vote. In the meantime, Ben-Shaul says the showing at Berkeley was “very successful. People loved it.”

Ben-Shaul hopes to show Turbulence in Israel, perhaps at one of the country’s Cinematheques, though nothing has been finalized yet. For now, interactive movie fans will have to visit Ben-Shaul in his office at Tel Aviv University or watch a TV news clip and interview with Ben-Shaul on Israel’s Channel 10 which provides a hint of the richness of interactive moviemaking.

Beyond entertainment, interactive video might even help to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Ben-Shaul suggests. Interactivity, he says, “develops thinking for people who are in what seems like an intractable conflict. It can be a real therapeutic tool.”

This article originally appeared on Israel21c.